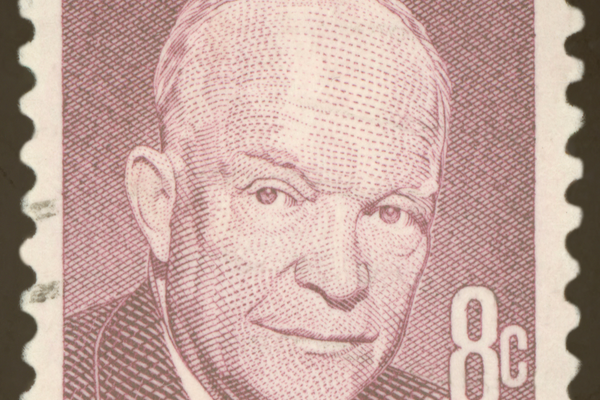

On November 4, 1952, the world watched as CBS News made a daring leap into the future of broadcasting with the help of a room-sized machine called UNIVAC. In an unprecedented move, CBS borrowed the computer to analyze early election returns in the tight race between Dwight D. Eisenhower and Adlai Stevenson. While the public tuned in expecting old-school political punditry, what they got instead was the first glimpse of how data-driven technology would revolutionize decision-making in real time.

The UNIVAC (Universal Automatic Computer), developed by J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchly, was a pioneering feat of engineering. It could process thousands of calculations per second using vacuum tubes and magnetic tape.

While it was built for scientific and military applications, its debut in political journalism is what turned heads.

The Machine That Knew

As election night unfolded, UNIVAC analyzed a small sample of early voting returns and confidently predicted a landslide win for Eisenhower. Yet this flew in the face of established opinion polls, which leaned heavily toward Stevenson.

Anchors Walter Cronkite and Charles Collingwood were skeptical. The computer’s prediction was so contrary to expert consensus that CBS delayed sharing its results with the audience.

Eventually, the numbers spoke for themselves.

Eisenhower won decisively, just as UNIVAC had forecasted. The delayed broadcast of the prediction became a moment of journalistic self-reflection on the promise and the discomfort of trusting machines over human intuition.

In hindsight, it was a triumph of computing power and a defining moment for data science in media.

UNIVAC’s Legacy and the Birth of Data-Driven Media

The 1952 election was the beginning of a technological revolution in journalism.

UNIVAC’s success proved that computers could interpret, predict, and inform.

Over the decades, this breakthrough paved the way for everything from real-time election tracking and predictive analytics to today’s AI-assisted journalism.

Modern newsrooms rely heavily on data modeling, not just during elections but in everyday reporting. The seeds planted by UNIVAC have grown into an era where machine learning models and computer algorithms are trusted partners in the newsroom, guiding both coverage and public understanding.

The Wrap

Seventy-three years later, the 1952 UNIVAC prediction stands as a bold intersection of technology, media, and public trust.

What started as an experiment became a cornerstone of modern political reporting, proving that even when machines contradict the experts, sometimes it’s the data that knows best.

In honoring this anniversary, we remember the moment television and technology first teamed up to change how we see the future.